Daughter of an epoch enlightened by the Renaissance and marked by political and religious contrasts, Artemisia Gentileschi breathed creative atmosphere from childhood on, undergoing, through her father Orazio, the fascinating discipline of painting, coming to conceive her own, equally sublime technique.

With a vast amount of material at her disposal on which to test herself and perfecting her natural talent, Artemisia was shaped by Caravaggio’s work; an influence her father had already assimilated, having himself established relations of acquaintance with the master Michelangelo Merisi, of whom, it is said, he often bought bases for his own compositions.

In this way, his daughter developed a peculiar style that became a tightrope walk between dreamy abstraction and pragmatic realism; never lacking basic historical-artistic context, given Orazio’s predilection for paying attention to contemporary artistic movements. Always narrative dense works, Artemisia Gentileschi’s paintings depict episodes from Greek mythology, the biblical accounts of David and Bathsheba, Lot, Lucretia, as well as the repeated theme of Judith.

Mary Magdalene was a subject very much loved by artists and the public alike, because she represents the ideal model of the search for virtue and the renunciation of world pleasures. The protagonist is depicted full-length, wrapped into a golden yellow dress, generously covering her knees, enhanced by the contrasting colours of the tunic as well as the rough foot with dirty nails sticking out of the dress, making it the focal point of the viewer’s gaze. Seated in a moment of meditation and prayer, with flushed cheeks, Magdalene turns her visage to her left, at the moment of her transition: in the foreground, a skull rests on a book upon a rocky surface, symbolizing departure from a life of sin.

We note some striking similarities with Caravaggio’s Magdalene in Ecstasy, in the position and modelling of the hands, as well as in the apparition of the cross in the upper left part of the canvas. The scene takes place on some kind of rocky formation, as gentle waves caress the sea in the background.

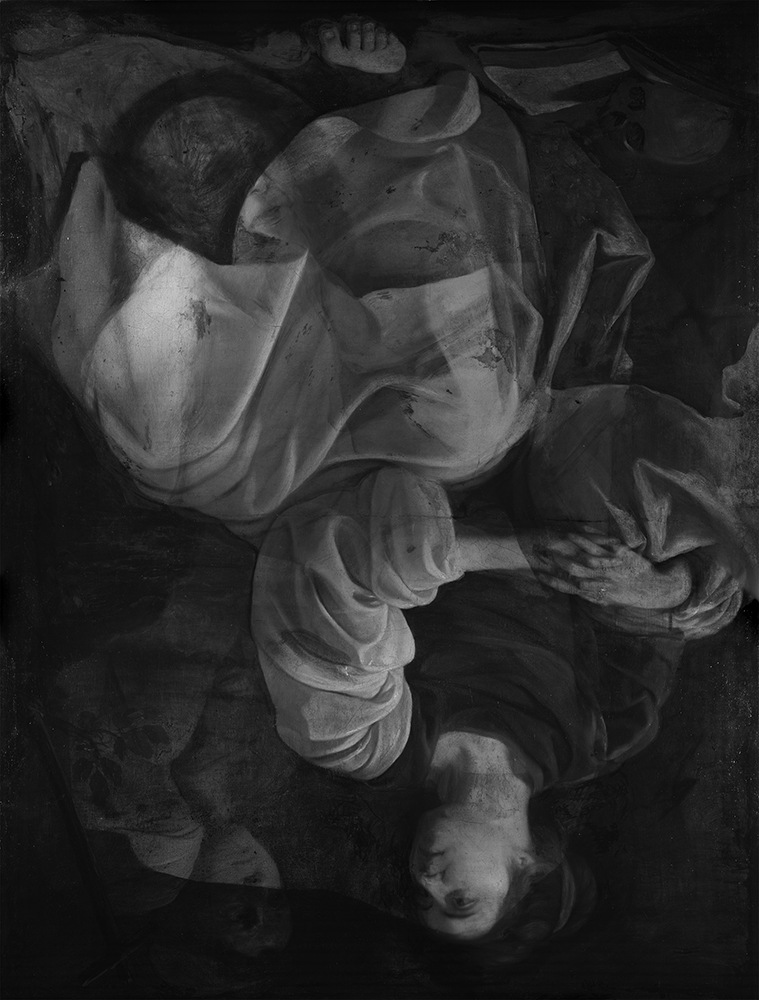

The paint layer is executed on a homogeneous and relatively thick red-brown preparation over the entire surface, especially visible on the upper right part of the canvas because of increased transparencies caused by the ageing of the polymeric film. In the same area, a figure, which was originally not part of the final painting but rather from another, previous, composition, appears as a ghostly vision.

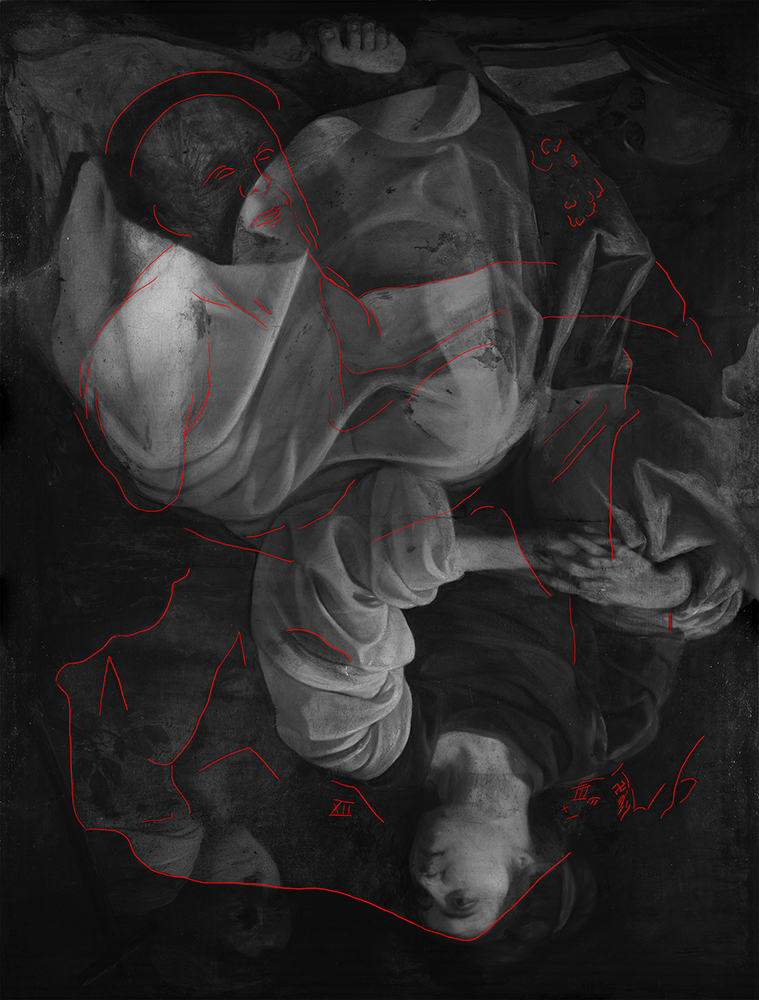

This phenomenon, coupled with infrared capture using our Apollo camera, have confirmed the presence of one or several other design made before the one currently visible : when turned upside down, the canvas reveals what could possibly be a Saint Jerome, seated, holding some kind of book or object, surrounded by vegetation. On the lower part, some annotations made by the artist and some vandalism.

Artemisia evidently reused this already started canvas, as did many artists of the period, to save on materials.

Image and text credits to Arcanes. Infrared reflectograms in this case study were taken by Apollo from Opus. Please get in touch via the enquiry form below to find out more.